Colombia: a Nature Superpower

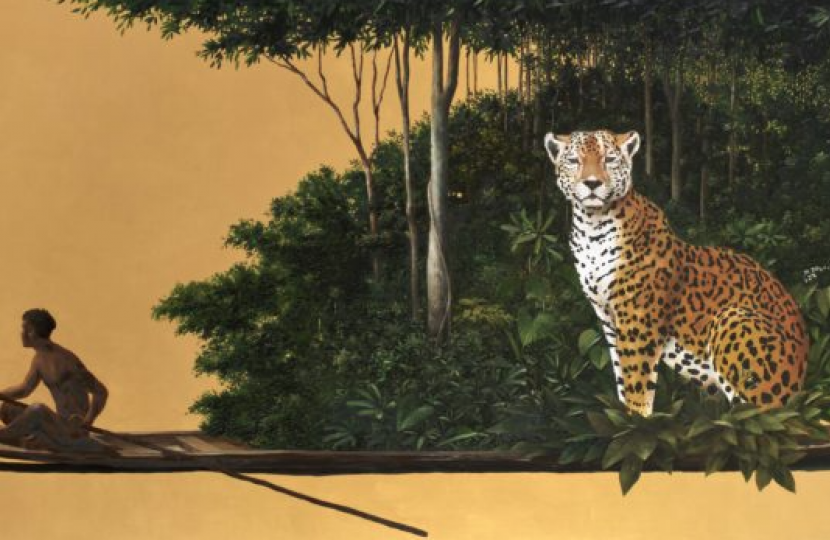

Gran Tigre Mariposa (Oro Derivados) 100x200cm Oil and Acrilic on Canvas 2011

A few weeks before the all-important climate COP in Glasgow, I found myself travelling to Colombia to meet the country’s President Duque and find ways in which we could enlist his support to boost ambition on nature and forests.

Nature has always been neglected in global climate politics, relegated at best to the margins of the margins. Of all global public climate finance, just three per cent has been spent on nature. It makes no sense given that there is no credible pathway to tackling climate change without massive efforts to protect and restore nature. Deforestation and destructive land use contributes nearly a quarter of all emissions. Nor can we help the most climate-vulnerable countries adapt to cope with climate change without nature. Compare mangroves with concrete defences: mangroves cost thousands of times less to install, they last forever, they boost biodiversity and local fish stocks, they absorb carbon and they shield communities from the ever-increasing storm surges.

So as Presidents of COP26, it was our ambition and my role to bring nature to the heart of the global response to climate. And that meant working with ambitious countries to build momentum.

Colombia is a biodiversity and climate superpower. It is one of the world’s ‘megadiverse’ countries, with nearly ten per cent of the world’s biodiversity and more than 300 distinct ecosystems. There are more bird species in Colombia than any other country on earth. A few weeks ago I had the immense privilege of visiting that country for the first time, and meeting both the country’s leaders and people from all walks of life. And I was deeply inspired.

Colombia’s forests, land and seascapes are almost indescribably beautiful. On the way back to Bogotá from a meeting of Amazon country leaders assembled by President Duque to agree steps to protect the Amazon, I stopped at Chiribiquete. Chiribiquete is the world’s largest tropical rainforest national park, stretching out over 43,000 km², with indigenous communities that have chosen to have no contact with the outside world. It is one of the few remaining places on our planet that is almost completely unexplored and unaffected by the modern world. There are no roads, no modern pathways, no real access. That inaccessibility is illustrated by the discovery only two years ago of some 75,000 prehistoric figures painted across cliff faces stretching over nearly eight miles here in the heart of Colombia’s jungle. Dating from 20,000 BCE and painted with reddish terracotta and ochre-coloured mineral-based materials, they include battles, dances, ceremonies and hunting scenes as well as flora and fauna with a particular focus on the jaguar, a symbol of power and fertility. Some of the images include now-extinct ice age species like the mastodon, the elephant’s prehistoric relative (absent in South America for some 12,000 years).

The site has been described as ‘the Cistine Chapel of the Ancients’ and is considered sacred by indigenous communities in the region who refer to it as the ‘Maloca (‘dwelling’) of the Jaguar’. On paper it is deeply inspiring. But actually being there at the heart of the reserve atop one of the famous tepuis – table-top mountains that rise up from the flats below – surrounded by rainforest, savannas and rivers, hearing a cacophony of wild sounds, seeing nothing whatsoever that betrays in any way the carnage done to forests and ecosystems elsewhere, simply defies description. It is a rare privilege to visit Chiribiquete, and one that will remain a highlight of my life.

I was inspired too by the people I met. From city mayors to community leaders, from school children to their teachers – everyone I met shared the same passion for their environment and commitment to protecting it. And I believe that is no less true of Colombia’s President Duque and his Environment Minister, Carlos Correa, who is leading the country’s environmental efforts. Their pride in Colombia’s natural treasures is understandable and their work both to protect and restore them is a model many other countries would do well to emulate: precious corals and mangroves being restored by local fishing communities to insulate coastlines and boost biodiversity; programmes involving local communities protecting the Amazon and regenerating degraded lands.

My visit to Colombia was timed to coincide with the run-up to the climate COP26 in Glasgow. And though of course we did not secure all the commitments we wanted from world leaders, the COP represented a genuine turning point on numerous levels. In particular, it was the first such COP that fully recognised the critical importance of nature in tackling climate change. We saw landmark commitments by world leaders on the second day, and nature truly was brought in from the margins of the conversation into the heart of our response to climate change.

More than 140 countries representing over ninety per cent of the world’s forests committed to halt and reverse forest loss and land degradation by 2030. Donor countries and philanthropists put unprecedented levels of finance on the table: almost USD$20m. We saw hard-won commitments from all the main Multilateral Development Banks – including the World Bank – to align their portfolios not only with the Paris goals, but with nature. There was a commitment from the world’s biggest buyers of agricultural commodities that their buying policies will be aligned with 1.5 degrees and our overall deforestation goals. And we had commitments from financial institutions with nearly USD$9 trillion in assets that they, too, will align their portfolios with these same deforestation goals.

Crucially, we also secured financial commitments to support indigenous people and help local communities protect their homes. It is not a coincidence that eighty per cent of forest biodiversity can be found in indigenous lands; they have protected those lands for generations and often in the face of threats to their lives. With the nearly USD$2 billion secured, so too can land tenure for indigenous communities be secured. And given the huge importance to all of us of extensive biomes of the Congo Basin, Indonesia and the Amazon, funds were secured alongside national commitments to protect and restore those areas too. The UK committed at least £300m to support Colombia and other Amazon countries in their efforts to protect and restore their forests.

Individually, these were big commitments, each of them bigger by far than anything we have seen before. Combined, they are bigger still, with each part reinforcing the other. It was, for example, the very strong signal from the commodity buyers that enabled us to get some of the more reluctant forest countries over the line. Above all, it was the inspiring leadership of big-ocean biodiverse forest countries like Colombia that made it possible for the UK Presidency to ask others to reimagine what is possible. The commitment and energy of countries like Costa Rica, Gabon, Pakistan and, of course, Colombia was visibly infectious and encouraged others to step up.

So alongside the big announcements on forests and land use, and before the formal negotiations even began, there were other world- leading commitments. President Duque, for instance, announced at COP that Colombia, Panama, Ecuador and Costa Rica will be creating a single coherent and connected marine protected area covering more than 500,000 km² of ocean – protecting key migratory routes for sea turtles, whales, sharks, and rays and boosting commercial stocks in surrounding waters. It is exactly that level of ambition and leadership the world needs, and I’m looking forward to the UK actively supporting this wonderful initiative.

What was secured for our forests at COP26 in Glasgow represents the turning point we urgently need. But we know that the gap between where we are now and where we need to be by the end of this decade is vast – and that promises are only valuable in so far as they are honoured. So in the year of our COP Presidency – and beyond – the UK will do everything we can to maintain momentum, inject real accountability and catalyse action. I have no doubt that the powerful partnership between the UK and Colombia will continue to be at the forefront of making that happen.

15 December 2021

The London Magazine